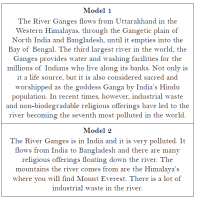

The diagram above by Oliver Caviglioli is one of the most useful diagrams I have come across for teachers. I wish I would have seen it when I started teaching! I think it summarises the learning process beautifully and is invaluable when it comes to thinking about and planning how we teach. It’s a great reminder of a number of key ideas from cognitive science:

- We need to do everything we can to ensure that the attention of our students is focused on the thing we want them to be learning.

- Our aim as teachers is to get things into the working memory and then to the long term memory. An understanding of Cognitive Load theory is essential for this.

- Long term memory is an interconnected and well-organised network of all the ideas and knowledge we know – called schema (represented by the cauliflower poking out of the head in the diagram!).

- We remember things by linking them onto our existing schema. For example, as a biologist I have a good and existing schema around immunity and vaccinations. So when I hear about the new COVID vaccination, I can make sense of this quickly and remember it, because I graft it on to this existing schema.

- If we don’t retrieve things from our long-term memory on a regular basis, we forget them. So regular retrieval practice is an essential part of strengthening memory. In the words of Daniel Willingham, ‘Memory is the residue of thought‘.

It’s really powerful to have an understanding of this as a teacher, as it will benefit the learning of all the students we teach. It’s particularly important to be using this to understand the challenges to learning that our students who are educationally disadvantaged will be facing. I am fortunate to work with Marc Rowland, who works with hundreds of schools up and down the country on this. Marc encourages school leaders to think about the following question:

“How does educational disadvantage affect the learning of pupils in our school?”

This encourages us to think about our disadvantaged students as individuals, understand the challenges they are facing as individuals and then think about how our teaching can support this. This is different from the less effective approach of seeing disadvantaged students as a homogenous group, with the same issues that will be solved by a common approach.

So what might these challenges be and how can we use what we know about learning to address them?

Struggling to pay attention – For some students, paying attention in lessons and focusing on the information that the teacher is delivering will be challenging. Rather than leaving this to chance and hoping that it will improve, there are some explicit approaches we can employ that will help with this. In this blog Jack Tavassoly-Marsh suggests the following areas to focus on, in order to support attention:

- How students enter the classroom

- Under what conditions the first task is carried out

- How a teacher gains whole-class attention

- How students should participate in paired discussion

- How students should work during independent practice

- How students should listen during question and answer phases

- How a teacher transitions from the instructional phase to students working

- Using questioning strategies such as ‘cold call’, ‘no opt out’ and ‘right is right’

- How students exit the classroom

Supporting a limited working memory – evidence suggests that the capacity of our working memory is probably fixed and will be more limited in some people than others. So for example, whilst some people might struggle to cope with managing 2-3 pieces of information at any one time, others might be OK with 4-5. If we know this to be the case for some of our students, we can support them with this. In this blog, Andy Tharby explains how, for example:

1. Outsource working memory by providing scaffolding that fades away incrementally.

2. Provide the conditions that help students to practise key skills and concepts to automaticity.

3. Centralise the development of long-term memory through careful curriculum planning.

This matters because if the working memory becomes overloaded then new information is less likely to enter the long-term memory. Andy then goes on to discuss approaches we can employ in our lessons to support this further, for example:

- Teaching in short bursts.

- Avoiding split attention.

- Reducing redundant information on lesson resources.

- Using worked examples.

- Presenting new information verbally and visually

Limited background knowledge and vocabulary – for those students who are educationally disadvantaged, it is possible that their schema will be less developed than their peers from a more advantaged background. This will certainly be the case if they haven’t been encouraged to read widely and just generally discuss the world around them. This will make it more challenging to grow and develop their long-term memory and the rich vocabulary that is so important if they are going to be successful and confident learners. We can support this by carefully scaffolding our questioning of these students to elicit this knowledge and supporting them to activate the prior knowledge they need to access the new material. In this blog, Alex Quigley shares some strategies we can use use to help students grow their vocabulary by building their schema.

These first points have clear implications for how we explain new ideas and knowledge to students:

- Break our explanations into chunks.

- Tether it what they already know.

- Keep it focused on what you want them to learn – avoid superfluous detail.

- Use worked examples.

- Use verbal and visual resources at the same time.

Limited thinking and limited retrieval – if students are not encouraged to review and discuss the work they do at school, at home, they will not be retrieving it from their long term memory and so over time, the material will soon be forgotten. There are ways we can support this:

- Ensuring our curriculum is coherent and well sequenced . It needs to be structured in such a way that there are opportunities to revisit and build upon key knowledge.

- Use low stakes quizzing at the start of lesson to retrieve key knowledge.

- Use Cornell note taking every lesson to support retrieval practice.

- Ensuring homework have an element of retrieval in them – not just for content that has been covered that week, but revisiting work that was done last month and last term. This will only be effective of course if there are strong processes and systems in place to ensure that students do their homework.

Will these approaches solve all the issues around educational disadvantage? No. It’s a complex problem, involving a variety of interconnected issues. What these approaches will do though, is give our teaching the best chance of being successful. This, combined with a ‘thousand little moments‘ will go a long way towards tackling the stubborn problem of educational disadvantage.