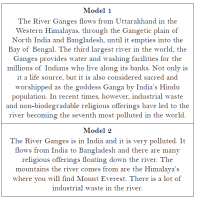

This term marks the first term that I have had trainee teachers take some of my classes. When giving them feedback, a similar reoccurring area of development arises – careful consideration of planning explanations as well as the explicit use of language when giving instruction. This is quite fitting considering my own focus as part of my instructional coaching this term is the very same thing.

In observations of their teaching, being sat among my students in the back of the room, like some trojan horse infiltrating their domain, I see an insight into their perspective, and things I have taken for granted in my own practice, especially the value of the explanations and instructions given to them. For a teacher such as myself who predominantly teaches GCSE students, I often take the students own intuition for granted when giving instructions. Year 10 and 11 students are usually better trained and have a better understanding of your practice and routines, so they already know what they must copy from the board and what is necessary and what is anecdotal. However, the value of contemplating one’s language when giving instructions has had a large impact on my KS3 classes.

One strategy I have incorporated comes from Doug Lemov’s Teach like a champion 2.0: Means of participation. Too often, especially with KS3 classes, where you’ve carefully considered your questioning, contemplated your pause time, remembered to ask the question first before targeting your student, all the recipes for good questioning… only to have the answer called out from your most enthusiastic student. Ruining the suspense and gravitas that comes with good questioning. The same student who wonders why instead of being praised for his excellent recall; he is being reprimanded for calling out.

Means of participation seeks to solve this issue, by clearly and explicitly telling students the criteria for participation beforeasking them a question. Instead of “Who can tell me what organelles are present in an animal cell” rephrasing the question to “By putting your hands up and not calling out, who can tell me what organelles are present in an animal cell?”. By doing this it gives clear and explicit boundaries for what is required for engaging in this part of the lesson. You are explicitly telling the students what behaviour you are looking for and using it as an invitation to participate in your lesson, helping to embed the behaviour until it becomes permanent.

By acknowledging the means of participations first, “Without putting your hands up, I’m going to ask someone, what is the function of ribosomes…” you are setting clear instructions for what students can expect to do to answer the next question, that those who do put their hands up will not be asked, and those who are not wishing to engage, are susceptible to being selected for this question. By giving the means of participation first, teachers also gain a more subtle way to challenge individuals who deviate from the instructions: by reminding pupils of the expectation previously mentioned. “Hands up, without calling out, who has the answer to number one”. If a student does call out, simply stating, “I did ask for you to put your hand up and not call out” this enables you to use polite and non-invasive interventions to reinforce expectations.

I have further adapted and incorporated this strategy into my non-questioning phases of the lesson. By giving simple explicit instructions before their task, I am giving them the means to participate with this portion of the lesson and ensure I have students fully understanding how to engage with what I have presented them.

“By writing down the question first, can you answer the question on the board”

“By working in silence, answer your starter questions on the board”

“One member of your group, by walking carefully, go get the equipment needed to start your practical”

This intervention, particularly with my KS3 classes, has enabled a much more settled atmosphere to my lessons. It has set clear expectations of the behaviour I am expecting and given me clear boundaries that allow me to easily set sanctions when those boundaries have been crossed. It also ensures that students are clear on what they are expected to do, and if I think they are not sure, I can follow up with questions to reiterate what I’m expecting.

“By working in silence. Answer your starter questions on the board while I do the register” …

“Alex… What am I expecting you to do, for these questions?”

“By copying the paragraph on the board, fill in the missing words” …

“Sam, how are you going to complete the task on the board?”

I have also found that by implementing this strategy it has become easier to ask follow-up questions. When the means of participation has not been clear, and several students have called out for the answer. It makes it much more difficult to ask another (or the same) student to develop or expand upon the answer given.

“By putting your hands up, what group does this element belong to?” then, with a follow up question “can you give me another example of an element in that group?”

By incorporating this simple addition to my practice, it has enabled me to not only create the appropriate culture in my class but has enable me to better establish what my expectations are for my students. It has made my KS3 students understand the clear boundaries for what is accepted in my class, I am seldom having to repeat myself or find myself frustrated that students have not grasped what I have asked them too. It has also enabled me to appreciate how the instructions that I have given are ambiguous and therefore causing more hurdles than my explanations have removed. It has provided a platform for the more reserved students to engage without being drowned out. By setting clear expectations that are public for all. It has ensured every student has equal footing in my class, that the two or three students calling out are not masking the 10 students who don’t understand. As well as helping those who are following and engaging with the lesson, to have the best possible environment to do so.

Research School Associate.

Pingback: A CPD Curriculum in 9 Principles | Ben Newmark