As students return to school later this month, teachers and school leaders up and down the country are thinking carefully about curriculum changes and lesson strategies to use that will best support post-lockdown learning. This is no easy task, and perhaps one of the greatest challenges is that there will be huge variation in students’ experiences and knowledge when they return to our classrooms.

For some, remote teaching has been a resounding success: These students have enjoyed taking control in a low-stress environment with the kitchen fridge not far away. For others, the experience has been a long, hard and lonely slog. These students have ploughed through the work, but success equates to completion rather than quality. Finally, we have students for whom their learning very much depends on school structures, and when this support goes so does any chance of academic success.

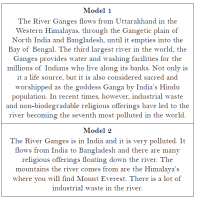

How does this link to knowledge organisers?

Over the past few years, the curriculum teams at Durrington have put impressive effort into producing high-quality knowledge organisers for every year group. You can read more about our journey with knowledge organisers here. In a nutshell, however, for us the purpose of a knowledge organiser is to support, rather than replace, teaching practices that we know work. Primarily, this means using knowledge organisers for retrieval practice, i.e. helping students store important facts and ideas in their long-term memory ready to use when tackling complex learning tasks in their working memory. When used in this way, knowledge organisers can be an incredibly effective learning tool that helps to ensure all students have access to the knowledge that a curriculum team have agreed is essential for their subject. Accordingly, knowledge organisers also have potential to be harnessed for ‘recovery teaching’, or in other words to help mitigate the problems that could occur as a result of the disparity between students in their remote learning experience. Below are five suggestions for how this might work.

1. Identify what students know and don’t know through retrieval tasks.

This does not differ all that much from how knowledge organisers were commonly used in the classroom in the pre-Covid 19 era. In order to a) ascertain what students currently know and don’t know and b) help students to polish up any knowledge that has become rusty over the past few months, retrieval tasks such as low-stake quizzes and questioning will be key. Knowledge organisers can work perfectly for this type of task, especially if they are set out using numbered grids that can be blanked out either on paper (handy if you are moving classrooms and need a ‘do now’ task that’s not technology reliant) or on the screen ready for testing. It would be advisable to test the content of a knowledge organiser in chunks for accurate, diagnostic assessment of the exact gaps in students’ knowledge.

2. Activate prior knowledge.

As Chris Runeckles explains in this blog, paying particular attention to activating prior knowledge before introducing new information will be crucial when trying to meet the needs of a divergent group of students. It may well be the case that, for some students, the knowledge required to access the upcoming lesson simply isn’t there yet whereas for others it needs a little fine tuning. Knowledge organisers can help to make this very easy. For example, you could ask students to identify for themselves what they know and don’t know by highlighting sections of the knowledge organiser – a few pertinent questions here would be prudent to check the students are accurate in their diagnosis. Alternatively, the knowledge organiser can also work as a beneficial aide-memoire for teachers to clarify what they should prioritise in terms of checking students’ understanding before moving on to new material.

3. Scaffold work in the classroom and at home.

Not only do knowledge organisers provide a means by which curriculum teams can ensure consistency and fidelity to their agreed curriculum, but they can also save hours of work by providing different layers of support in the classroom and for homework. Once you feel confident about the gaps in individual students’ knowledge, it is very easy to direct them to specific sections of a knowledge organiser to scaffold their learning. For example, a student in MFL who has forgotten how to change regular verbs to the past tense can use a section of a knowledge organiser to remind them of these grammar rules as they work. It would be imperative, of course, to remove this scaffolding over time. Whilst the targeted differentiation offered by a teacher is irreplaceable, in the first instance of post-Covid 19 teaching where the gaps are likely to be wide-ranging in any one class, strategies like this are what will make knowledge organisers worth much more than the paper upon which they are written.

4. Explicitly teach students to self-monitor their work.

Among many of the sliver linings that have emerged from remote teaching, one of significance is that it has provided an opportunity for students to practice their self-monitoring skills. Away from the security blanket of a teacher’s presence, some students have become increasingly reliant on themselves to identify what they need to complete a task, how they should go about doing this and how to check what they have got right and wrong ready to improve their work next time. This is good news and something we want to sustain when students return to school. Knowledge organisers can provide a ready-made method for encouraging students to sustain (or begin to) take control over their learning. For example, if asking students to complete an extended piece of work such as an essay or performance, using a knowledge-organiser as a checklist before, during and after the work can be a very successful way to get students planning, monitoring and evaluating.

5. Explicitly teach vocabulary.

At Durrington, one of the ‘active ingredients’ of all knowledge organisers is that they include either tier 2 or tier 3 vocabulary that will be explicitly taught to students as part of subject lessons. Emerging evidence on the effects of Covid-19 suggest that students’ literacy skills are most likely to be negatively impacted, especially those from a disadvantaged background (see EEF report on KS1 here). Robust research evidence makes it clear that explicitly teaching vocabulary is one of our strongest ‘best bets’ for tackling the huge literacy barrier that many students face. This becomes especially important now that students have been away from the academic language of the classroom for many weeks. Thus, reminding, reteaching and resetting expectations about vocabulary use should be one of our non-negotiable teaching priorities, and knowledge organisers provide a consistent starting point across curriculum teams for this focus.

Finally, don’t forget that knowledge organisers can incorporate procedural as well as declarative knowledge, that is knowledge of how to go about completing a piece of work. Students are just as likely to need support in getting back on track with methods, systems and practices as they are with the factual nuts and bolts of a subject. It is when these fundamentals are in place that the complex learning – making connections, comparison, synthesis, pattern spotting and prediction, for example – can begin.

Useful information. Thank you for sharing.