Last weekend a twitter conversation resulted in our teaching ‘Big 4’ evolving into 5 – Challenge, explanation, modelling, questioning & feedback. More can be read on this here. If I’m honest, I haven’t really given a huge amount of thought to ‘explanation’ – it was just something I did as a teacher – told them what they needed to know! It was for this reason that I realised I should probably give it some more thought and make a concerted effort to get better at it – through deliberate practice. With this in mind, I was pleased when late last night, David Didau tweeted a link to this article by Chip & Dan Heath:

DD said it was impressive – so I took a look (he tends to know what he’s talking about….most of the time!) He was right – it gives a great summary of their book ‘Made to Stick’. The full article can be downloaded here. In the introduction they say:

“A sticky idea is an idea that’s understood, that’s remembered, and that changes something (opinions, behaviors, values). As a teacher, you’re on the front lines of stickiness. Every single day, you’ve got to wake up in the morning and go make ideas stick. And let’s face it, this is no easy mission. Few students burst into the classroom, giddy with anticipation, ready for the latest lesson on punctuation, polynomials or pilgrims.

Here’s the good new about stickiness: This isn’t just interesting trivia about how the world of ideas works. Rather, it’s a playbook. There are very practical ways that you can make your teaching stickier.”

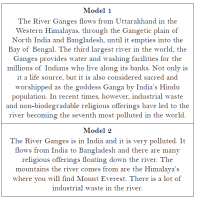

The article then talks about 6 traits that make ideas stickier. I’ve tried to summarise each one here:

So I thought I’d try and put this into action – fortunately I had two Y11 lessons today, introducing the idea of nuclear radiation. A perfect opportunity to practise stickiness. This is what I did:

- Simple – I anchored it on to their existing knowledge of the atom, by getting them to draw and explain the structure of the atom, which we then shared and discussed. This would then lead on to two key concepts for the lesson – be able to describe and explain Rutherford’s scattering experiment and what an isotope is. This is definitely not about dumbing down or lowering expectations. It’s about distilling complex ideas into the key ideas and then using what they already know to build up to these complex ideas. In his article on explanation (see below) David makes the point of how important it is to use specialist academic language here – and insist that students do too.

- Unexpected – In order to get them curious, we looked at photos of Chernobyl and posed the question, how could these tiny atoms cause such devastation? This is the gap in their knowledge that we were going to fill, having opened it. They were curious!

- Concrete – Rutherford’s scattering experiment is very conceptual, so I demonstrated it by throwing squash balls at footballs. They bounced off, in the same way that early scientists expected the alpha particles to do when they hit the ‘plum pudding’ atoms. This led on to a discussion about what it meant when the alpha particles went straight through?

- Credible – The photos of Chernobyl helped with this, as it made the issue very real. This can also be backed up by statistics e.g. claims that Chernobyl won’t be fit for human habitation for 20 000 years. However, this will be returned to next lesson, when we get out the radioactive sources and the Geiger counter. Students will see that objects emit radiation.

- Emotional – The photos of people who had been affected by Chernobyl (mutations) certainly made them feel for the people. The ’emotional’ trait can also be developed by making students feel aspirational, as described in this brilliant example from the article:

- Story – Science provides loads of opportunities to tell stories – and the story of Rutherford’s scattering experiment was no exception. It also resulted in some great questions from the students about ‘How science works’ e.g. Why didn’t he just believe the plum pudding idea? What made him think of this experiment? Did he do any other experiments? Did people believe him? How do we know he’s right? Brilliant fodder for the science teacher!

It didn’t take me long to think through these 6 traits and I think that this could be a really useful ‘planning checklist’ for any teacher looking to develop their explanations. Will you be able to do all 6 in each lesson? Probably not. But over a series of lessons, almost certainly yes. Whilst I can see how it will work really well in science, I’m interested to hear how people feel it will apply to their subjects?

David Didau has written a related article (which is also great) here.

Reblogged this on The Echo Chamber.

I think the bottom line is that kids remember lessons which emotionally engage them and / or encourage them to think, because most kids get very little chance to think carefully about issues in their everyday lives. I agree that stories are a great vehicle – perhaps the earliest method of teaching. .

BTW wasnt Elvis genius? I hadn’t actually seen this clip

An excellent blog Shan and as a fellow scientist I really enjoyed the lesson walk through. I’m part of a working party in school putting guidance together on 10 aspects of quality teaching. Could I take some aspects of this blog (credited of course) and include it in a section on teacher clarity (or even perhaps planning)?

It’s made me think. Explanations are just something we do. I know personally I haven’t spent much time thinking about maximising my explanations to ensure understanding and that as well as that the learning “sticks.”

Damian

Pingback: Explain please…. | Class Teaching

Pingback: Teaching that STICKS – Planning a ‘sticky’ lesson. | @mrocallaghan_edu

Pingback: Edssential » Making explanations stick

Pingback: What is good teaching? Sharing best practice across the School. | mrbenney