As part of a series of blogs focused on Durrington’s six teaching principles, this piece deals with the underpinning principle of explanation. It marries with James Crane’s blog on the Durrington Research School website.

According to the Collins English Dictionary ‘if you give an explanation of something, you give details about it or describe it so that it can be understood’. Whist this definition of explanation is simple enough, the myriad of students that make up a teacher’s audience can make this fundamental principle of teaching much more complicated than it seems. Factors such as the students’ background knowledge, their depth and breadth of vocabulary as well as their belief in you as a credible source of information can all hugely influence the efficacy of any teacher’s explanation.

Fortunately, there are some clear, practical strategies that every classroom teacher can use to ensure that their explanations enlighten the way through the muddy waters of learning rather than leaving students all at sea.

The Durrington Research Blog this week summarises the findings from the Department of Education’s recent paper ‘Cognitive Load Theory in Practice: Examples for the Classroom’. This paper provides seven teaching strategies that teachers can employ to help ensure that students’ working memories are neither dealing with too much cognitive load nor too little. When this balance in explanation is struck, students’ learning is optimised.

Strategy 1: Tailor lessons to students’ existing knowledge and skill.

A key element of effective explanation is to tether new knowledge to what is already known. Ways to do this in the classroom include making comparisons, using analogies and using concrete examples. A recent example from Durrington comes from an English teacher explaining the meaning of the word ‘imperceptibly’ to a Year 10 class. This is a tricky concept to elucidate that could result in a very convoluted and abstract discussion about the tangibility of observational matter. Instead, the teacher explained how fingernails are examples of something that grow imperceptibly, that is something that definitely happens over time but without you noticing until a later stage. The use of a concrete example, to which all students could relate, pinned this slippery idea to rock solid understanding.

Strategy 2: Use worked examples to teach students new content or skills.

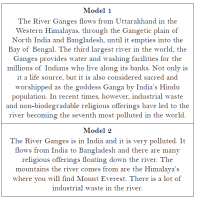

Worked examples provide students with fully guided instruction by labelling every step of the process required to solve a problem or successfully complete a task. This strategy helps to free up students’ working memory and allows them to focus on the process. In turn, this means they are more likely to be able to solve a problem using the same process later on. An example from Durrington comes from a history lesson on the Cold War. The teacher wrote an exemplar paragraph step by step on the board, labelling each step as he went. The teacher then left this labelled example visible for the students on the board and presented a new (but similar style) question for them to complete.

Strategy 3: Gradually increase independent problem-solving as students become more proficient.

Fully-guided instruction is useful for teaching new material but can become less effective as students increase their proficiency. Eventually, students need to be pushed into their struggle zone (see last week’s blog on ‘challenge’) by practising independently. The process of removing explanation in the form of scaffolding is a finely-tuned one involving very accurate knowledge of how expert students have become with specific skills. One approach that we use at Durrington is the ‘I – we – you’ model. In the first step of this strategy, the teacher models how to successfully complete a task or solve a problem. This involves the teacher thinking aloud and thereby explaining the questions, decisions and checks that she is making as she works. There is no input from students at this stage – their job is to do as the teacher is doing: watching, listening and recording what happens. In the ‘we’ stage the teacher presents a new but similar task and this time questions the students very carefully on what she should do to complete this successfully. The questions will probably be about the procedure, for example ‘How do I start?’, ‘What do I need to remember to do at this point?’ etc. From this questioning, the teacher must judge where she needs to step in with direct guidance because there is a knowledge gap or misconception, or where it would be more beneficial for the students to think hard about the process for themselves. In the final ‘you’ stage, the students complete a new but similar task independently. The teacher can use this feedback to identify if any parts of the process need explaining and modelling again.

Strategy 4: Cut out inessential information.

On average, we can only hold around seven chunks of new information in our working memory. This means that teachers need to think very carefully about the details they are providing in an explanation of material to students and minimise anything that is not relevant. Ways of doing this include:

- Thinking carefully about PowerPoint presentations and avoiding images or words that do not directly contribute to an understanding of the material.

- Not presenting students with words on a PowerPoint and speaking to the class at the same time. A better strategy would be to allow the students to read independently, or read aloud with no visual presentation of words.

- If students have been studying material for a long time, minimising resources that are based on knowledge they have already secured. This will free up students’ working memories so that they can focus on the next stage of learning.

Strategy 5: Present all the essential information together

A key aim of explanation is to avoid the split-attention effect. This is when students have to divide their attention between two or more sources of information that have been presented effectively but can only be understood in reference to each other. The English Department at Durrington have recently been developing resources with this strategy in mind. Year 11 students have been practising their extended transactional writing pieces with a particular focus on structuring their writing effectively. To support the explanation of how these pieces should be constructed, every student is provided with examples, with the labels integrated in the model (rather than on a separate resource or different page) to show how the structuring strategy works in the piece.

Strategy 6: Simplify complex information by presenting it orally and visually.

Our working memory has two separate ‘channels’ that can cope with visual information and auditory information. If information is spread across the auditory and visual channels at once, the cognitive load can be better managed by the student. Ways to enact this strategy include using images to support verbal descriptions (as long as the images are directly linked to the explanation) and summarising key ideas in a diagram. Our Geography department make excellent use of this strategy through their case study diagrams, which you can read about here.

Strategy 7: Encourage students to visualise concepts and procedures they have learned.

This is a strategy for when students have already been taught the necessary declarative or procedural knowledge and have a very secure and accurate understanding. The aim is for students to mentally visualise themselves carrying out a task or solving a problem. The process of visualising helps to make this knowledge automatic by storing it in the long-term memory. For example, imagine a teacher has spent considerable time taking students through the process of answering a 6 mark question in PE. The subject knowledge has been taught as well as the steps to answering this type of question, and this has been practised many times. With visualisation, the PE teacher may present the students with a new 6 mark question and ask them to imagine every step they would take to answer the question. This strategy can be an effective way of gradually removing guidance on the way to independence.

Posted by Fran Haynes.

Lovely Fran!