This morning Michael Chiles asked a question on twitter on whether it was sensible for an observer to make a judgement about the pace of a lesson:

This reminded me of a consultant that I worked with as a young head of science back in the 90s whose mantra was that teaching was good when the pitch, pace and progression were all evident in a lesson. This wasn’t just the view of this consultant, but was very much viewed as the accepted wisdom back in the day – but it would seem that this view, like many bad ideas, has lingered and still exists.

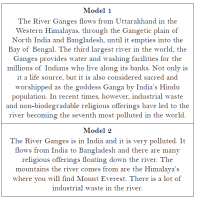

Now to clarify, pitch, pace and progression are all things that are worthy of consideration when talking about teaching. However, the problem was the view of what was good in terms of the 3Ps was not helpful. It went something like this:

- Pitch – the lesson should be pitched at the right level for all students in the class.

- Pace – lessons should be pacey and students should be moved from one activity to another swiftly.

- Progression – it should be possible to demonstrate the progress that has been made in learning throughout the lesson.

Now, it would seem that (thankfully) most educators have dismissed this view of what makes good teaching. Or so it would seem. There are still stories of lessons being observed through this kind of lens and judgements being made about teaching and teachers, based on this view of teaching. This really is not helpful and here’s why:

Pitch

How can a teacher possibly plan 25 or so different lessons to cater for the different prior knowledge of every student in the class? Furthermore, if a low attaining student is simply given ‘easy work’ how are they every going to be challenged to think and improve? They will simply stay at the level where they started.

A much better approach is to have high expectations of all students, teach to the top and use careful modelling, questioning and feedback to challenge all students to think about the subject content being delivered This is what we need to be aiming for, because we remember what we have to think about – in the words of Daniel Willingham:

‘Memory is the residue of thought’

Tom Sherrington has written about the approach of teaching to the top here.

Pace

Learning takes time and requires purposeful practice. Students need to be given time to practise what they have been taught, make mistakes, learn from their mistakes and then embed this new knowledge and skill over time – and then repeat it. In ‘The Hidden Lives of Learners’ by Graham Nuthall, he suggests that students should be exposed to new content at least three times if they are going to be able to commit it to their long term memory. How on earth can they do this if they are rushed through tasks and then swiftly moved on to another activity? They can’t.

By the same token, if I was to spend two weeks teaching my students the word equation for photosynthesis, then I could be rightly criticised for dragging something out for too long! So yes, pace matters, but what matters is the appropriateness of the pace. Students need to be given enough time to embed what they have been taught.

If you’re interested in learning more about how research from cognitive science can be implemented in the classroom to support long term memory, take a look at our 3 day training programme.

Progression

The idea that learning can be somehow measured/judged in a lesson is just bonkers and deserves to be challenged whenever it comes up. In this post, David Didau explores how he defines learning:

“Learning is tripartite: it involves retention, transfer and change. It must be durable (it should last), flexible (it should be applicable in new and different contexts) and liminal (it stands at the threshold of knowing and not knowing).”

So learning results in a change in long term memory and happens over a long time. With this in mind, we can’t ‘see‘ learning – and certainly not in a lesson. We can see how students are performing on a particular task, but this isn’t the same as learning. If we really wanted to test if they have learnt something, we would have to revisit them in a few months or years to see if they can recall it from their long term memory and transfer it to a new context.

A much better conversation in terms of progression is how well sequenced the curriculum is, to allow students to progress in terms of the cumulative development of their knowledge. More on this here.

So, when talking about teaching let’s reframe our view of the 3Ps:

- Pitch – is the level of challenge such that all students will be required (and supported) to think during the lesson?

- Pace – will students be given enough time to practise and embed the new knowledge they are taught?

- Progression – is the curriculum well planned, sequential and cumulative in terms of knowledge development?

Posted by Shaun Allison

Pingback: What’s wrong with ‘pitch, pace and progression’? | Class Teaching – DT & Engineering Teaching Resources